The first thing anyone entering the Natural History Museum of London sees is Dippy, 26 meters tall. Next to this replica of a Diplodocus dinosaur, which lived 150 million years ago, people who fill the gallery this autumn morning look like ants.

We came to the museum to do a piece on the Angela Marmont Centre for UK Biodiversity and so we leave Dippy behind.

We turn left to a wood corridor, pass without stepping into the dinosaur and mammal galleries and arrive at Darwin Centre, where scientists are working in the museum collections. We come down some stairs and turn left. And there they are, the most beautiful doors, painted with butterflies, bees, flowers, bats, spiders and a robin. This is the right place. And Stuart Hine is already here to meet us.

The director of Angela Marmont Centre walks with us, along shelves full of books, nature posters on the walls – including one of the Azores birds, a Portuguese island -, tables with scientists bent over their computers, till the drawers with the fossil collection.

Stuart Hine has his vision glasses to close supported on his forehead as he speaks and he only puts them on to read the labels with the data of each fossil. “The collections visitors use the most are the insect and fossil collections”, says this naturalist, opening a drawer to pick a shark tooth found at the East coast of England. When we ask him if people can touch these fossils he looks at us as if it was necessary to find the obvious. “Of course! On most of the time we don’t need these specimens to identify what people brought us but it’s nice to bring them here and talk with them for a while.”

He tells us that, when people want to learn more, it’s more effective to show them the collections instead of just telling them which species they have brought. “These are the things that motivates people to use the natural history collections. They know they can come here and use these specimens for their own studies. And not just for top investigations; we are here for simple situations such as someone that has found a fossil on the beach and wants to know what it is”.

These specimens came from the main collection of the Natural History Museum of London. “We want to give people the best we’ve got. These specimens are not the ones the main collections don’t want because they are damaged”, Stuart Hine explains.

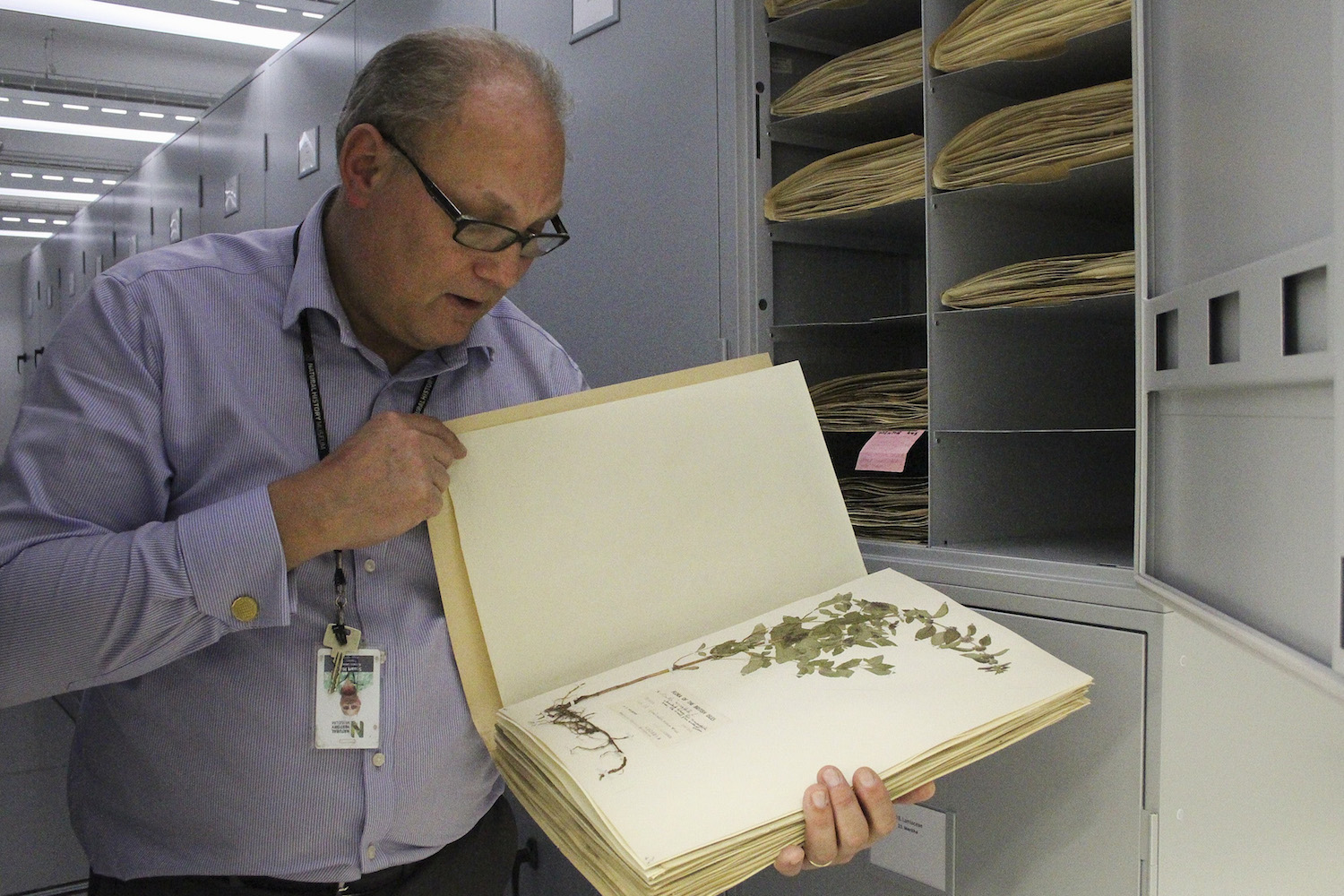

We would love to stay here and open each one of the fossil drawers but we have to go. Stuart Hine goes to his desk to pick up the key and then opens up one big door at the end of the room. It’s where the British herbarium is.

There are 6200 shelves full of herbarium sheets, with dry plants from each species. The majority has one hundred years old.

“People who have doubts regarding the plant they brought can come here, with supervision, and look in the herbarium”, he adds. Besides, “the plant curator is always at hand to help in the identification.”

The shelves with the insects are on the other side of the corridor.

“Anyone can come here. If they have never used any Natural History collection, we show them how to do it.” As he speaks, the director takes from the shelves boxes with glass covers and butterflies inside. “These collections should be available to anyone with valid investigation purposes, such as an academic or just someone who saw a television show with Sir David Attenborough on butterflies and simply wants to learn more about them.”

For Stuart Hine, “this is part of the reason why this museum was built, for people to understand what we do”.

As he saves the boxes with the butterflies he says: “this is a great opportunity to involve people, to inspire them. And all comes down to this: to ensure that there will be as much naturalists tomorrow as the ones we have today.”

[divider type=”thin”]

Now that you saw the backstage, read Stuart Hine’s interview here.