Last summer, between 470 and 550 stag beetles (Lucanus cervus) were found in Portuguese ancient oak forests and urban parks by the 500 participants in the first national census on the species. Now it’s easier to find out what to do to help Europe’s biggest beetle, an iconic and endangered insect.

In the stillness of the oak and chestnut woods lives the stag beetle, the biggest beetle in Europe. Male fights for territory are fascinating natural happenings, high in the tree brunches. The first beetle to fall down loses everything.

Still, fight for survival as a species is even more complex. The European stag beetle is classified as Near Threatened in the IUCN (International Union for Conservation of Nature) Red List. This species has lost much of its habitat in Portugal, as oak woods retreat. But what’s really happening?

Thirteen European countries – Belgium, France, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, Russia, Slovenia, Spain, Switzerland, Ukraine and the United Kingdom – created the European Stag Beetle Monitoring Network to try to know more about the population size, distribution and trends. The network was initiated in 2008 by researchers from eight countries, with a standard monitoring protocol. In 2016 the network was expanded and nowadays has transects in 13 countries all over the stag beetles range.

Portugal joined the team last year, in an effort that brought together students and researchers from the BioLiving association, the Wildlife Unit in the Biology Department of the Aveiro University, the Entomology Portuguese Society and the Nature Conservancy and Forests Institute (ICNF, in Portuguese).

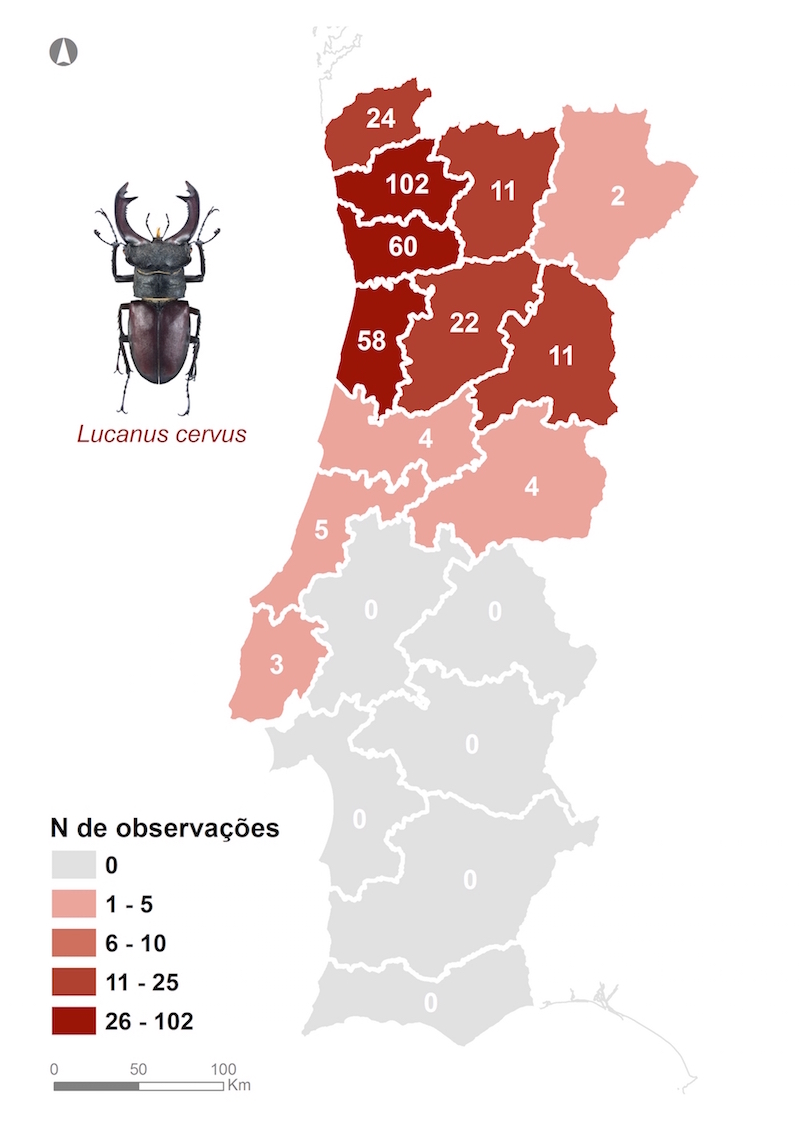

The monitoring – underwent last summer, specially in June and July – reported between 470 and 550 stag beetles.

Besides this species, the census also looked for two other beetle species. It registered 59 observations on Dorcus parallellipipedus and 23 on Lucanus barbarossa, both species without Portuguese common names.

In total, this census registered 552 beetles of these three species.

Of the four species on the Lucanidae family, which has in the stag beetle its ambassador, the first year of the census registered observations of three species; only the Platycerus spinifer, the smallest among them, remained unobserved.

João Gonçalo Soutinho, 21, is a recently graduated biologist and it’s the coordinator of the Portuguese Stag Beetle Monitoring Network. He told Wilder they received 564 observations by 485 people. These were sporadic observations. Besides these, six transects were done by six volunteers that submitted 38 sightings of stag beetles and five of Dorcus parallellipipedus.

The Park Rangers and the ICNF registered 55 observations of stag beetles and one of Dorcus parallellipipedus and the team that coordinated the census registered 37 stag beetles on their fieldwork visits.

“Most of the observations were made in the North and Centre North of Portugal”, being Braga, Porto and Aveiro the districts with the biggest numbers of beetles, he said.

The insects were found not only on woods but also on urban zones, especially in houses, roads and urban parks.

During the monitoring new locations were found for these beetles. Actually, 51%, 47% and 33% of the distribution areas that we now know of each species – stag beetle, Lucanus barbarossa and Dorcus parallellipipedus, respectively – were found in the first year of the monitoring.

“This tells us, for instance, that the scientific community knew too little about these species’ distribution”, João Gonçalo Soutinho said. “This gap in knowledge is a common problem regarding most of the invertebrates in our country, which makes even more urgent to move forward in the elaboration of red lists for Portuguese invertebrates.”

This year, new census

João Gonçalo Soutinho revealed that in 2017 is going to start the second year of this monitoring. “We need more years of monitoring to fully understand these species’ abundance and whether their populations are stable, decaying or increasing. This is a very important data to define priorities for conservation on a long term”, he added. Volunteer work will be crucial, once again.

As in 2016, this year the census will be happening in summer, especially in June and July, the peak of these insects activity. It’s in these months that the beetles turn themselves from caterpillar into the real beetle. In that moment, they leave behind three to four years of days spent inside dead wood, feeding on oak roots, usually big trees that either died or have dead parts. For that reason, these are animals that help regenerate the forest.

When the beetles emerge and see the light of day, they have one simple priority: look for a mate to reproduce. They are on a mission and will spend the energy reserves they accumulated as caterpillars. However, sometimes they can feed on the oak sap or on fruits.

This year, they will be in the spotlight once again.