There is a new host welcoming visitors to Vasco da Gama Aquarium, in Algés, Lisbon, at the new exhibition that started last November. This specimen with 120 years, preserved in formaldehyde, is a footballfish and it helps to tell a lesser-known part of king D. Carlos’ life, the penultimate Portuguese monarch (1863-1908).

It was the Portuguese monarch who captured this footballfish – living in the depths of the ocean, with its characteristic antenna hanging in front of its eyes – during the first expedition he organized, in 1896, to explore the depths of the sea between Cascais and Sesimbra.

The story of this trip and of the naturalist king who carried it out, and that in the following years undertook other 11 oceanic expeditions is now in the new exhibition in the Hall, just at the entrance of Vasco da Gama Aquarium.

“D. Carlos’s first oceanographic expedition celebrates now 120 years. We wanted to tell the naturalistic story of this king without being attached to his political history”, explains Maria Pitta, biologist of the Aquarium and responsible for the new exposition “The Prince who Dreamed about the Bottom of the Sea”.

Those who now enter the Hall learn that D. Carlos I was born in 1863, at a time of many scientific discoveries, when oceans were “the last great frontier” and some years before the adventures of “Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea” by Julio Verne were published (in 1870).

D. Carlos and his brother D. Afonso were educated “like ordinary children”. Since their early years they used to play on the beaches of Belém and Pedrouços”, says Paula Leandro, biologist and responsible for the department of cultural dissemination of the Aquarium.

The future king became increasingly interested in the depths of the sea after he met Prince Albert of Monaco, a European scientist who visited Lisbon when D. Carlos was only 15 years old. The friendship between them – which will also include the Azorean naturalist Afonso Chaves – would go on through out their lives.

Carlos began his oceanographic expeditions in 1896 aboard the yacht Amelia, seven years after he became king of Portugal. To exploit the seabed, till 1907, he uses several techniques.

“Most of the specimens you can see in this exhibition came from his first campaign”, Maria Pitta said.

All the specimens are more than 100 years old and they are perfectly preserved. Inside the showcases the king used for his own Natural History exhibitions, we can see, for example, the naturalized specimens of an imperial blackfish (Schedophilus ovalis), caught in the Sea of Cascais, in 1896, and of a grey-triggerfish (Balistes capriscus) captured in August 1899.

Aboard yacht Amelia, animals and other materials were stored in buckets of salt water, to prolong their lives. From there, they went to aquariums in the Citadel of Cascais, where many were treated and preserved in formaldehyde or alcohol.

Inside the original glass flasks, we can see urchins and a starfish, small sea-cucumbers, crabs, sponges, a sea-slug described by the king in his report of the first expedition and other curious specimens that the king liked to show the public.

Maria Pitta and Paula Leandro note that this king did real Science and never kept it for himself.

D. Carlos published a report on the trip and the main results after the first expedition and others that followed. He compiles notes and does useful studies for fisheries, such as one on tuna migration based on forms that ship-owners had to fill out.

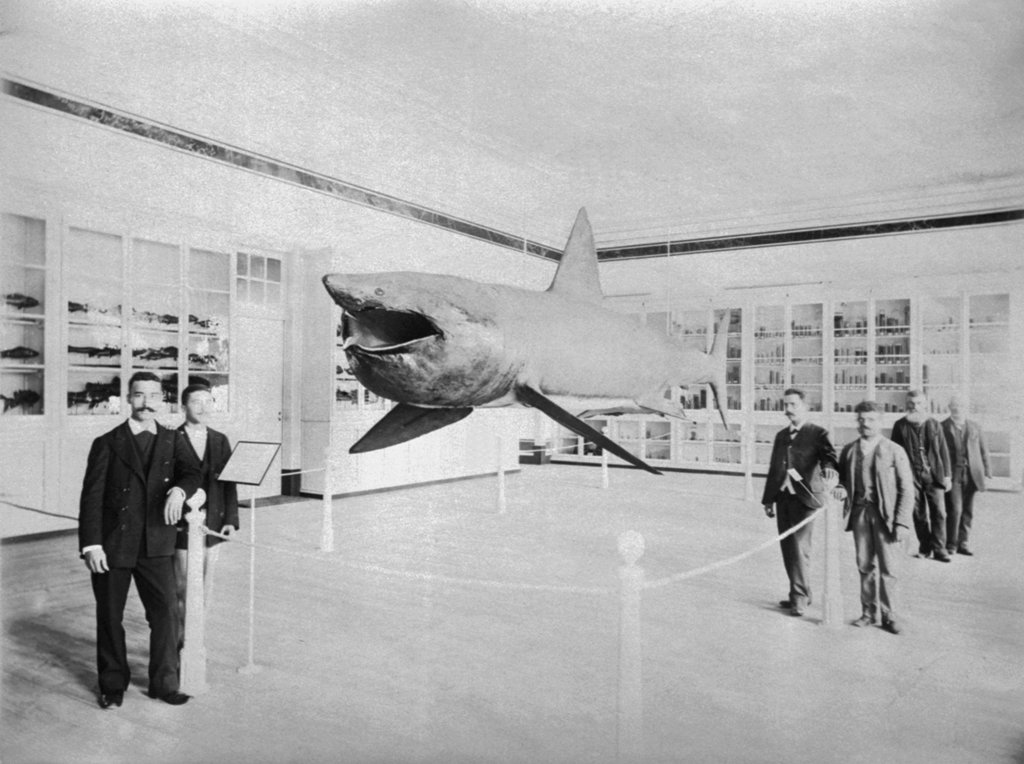

In 1897 the king set up an exhibition about the first oceanographic campaign at the Museum of Politechnic, now National Museum of Natural History and Science, followed by another at Vasco da Gama Aquarium, in 1898, which had just been inaugurated to commemorate the 400 years of the discovery of the sea way to India.

There, the general public could get to know many of the captured specimens, including some naturalized sharks as well as fishing equipments and scientific instruments.

The first exhibition as well as the others that followed it were guided by Albert Girard – born in New York, but living in Portugal since he was a child, curator of the royal collections at Necessidades Palace and scientific adviser to the king.

“D. Carlos had great esteem for Girard and the feeling was reciprocal”, said the marine biologist Luiz Saldanha (1937-1997), in a text published about the Portuguese king, whom he called “father of the Portuguese oceanography”.

Luiz Saldanha emphasized that “there was a true symbiosis” between them, which “led to considerable achievements”.

However, even without the presence of his counsellor, D. Carlos alone recognized many of the species he found or those the fishermen brought to him. And it was he who wrote the studies to be published.

“He was an excellent observer and had a very good visual memory, which are common traits for biologists and illustrators”, said the two biologists of Vasco da Gama Aquarium.

No wonder why the king also liked to paint, especially maritime themes. One of the exhibition’s pieces is the reproduction of the yatch Amelia, a vessel used in the first oceanographic expedition, painted in pastel by D. Carlos.

Visitors of the new exhibition can also see, for example, documents written by the king himself on his explorations and the illustration of a king-of-herrings (Trachipterus sp), also by D. Carlos. Until he died in 1908, he continued involved in the scientific study of the Portuguese sea and marine species.

These works, like the other documents and illustrations produced and commissioned by the king after the oceanographic expeditions carried out until 1907, are today in Vasco da Gama Aquarium. The same with the scientific books consulted by the monarch.

In total, there are about 600 documents in D. Carlos I Oceanographic Collection, delivered to the Aquarium in 1935 by the Portuguese Naval League, which also includes 2.200 specimens of the several thousand collected during the king’s expeditions, or which were delivered by fishermen; many of them were lost in the years after the fall of monarchy.

For the new exhibition, the Vasco da Gama Aquarium team worked with the company P-06 Atelier as authors of the museology and communication project, which included decoration of the staircase leading to the first floor. Here, surrounded by blue and in an atmosphere resembling the bottom of the sea, visitors can discover reproductions of king’s sentences and illustrations of marine species of books belonging to D. Carlos (and nowadays in the Aquarium).

The Hall itself was completely renewed, including the mural paintings, all with marine themes, according to Maria Pitta and Paula Leandro, who attribute the work to the company Esgrafito Mural.

The aim of the two biologists is to extend this new look to the rest of the museum and to the Natural History pieces it exhibits and that have long lived together with the live animals at the aquarium.